Authenticity is Key: How an Authentic Team Climate Can Save You From Burning Out

by Abigail Kinzel (2nd semester Master Psychology – Human Performance in Sociotechnical Systems, Dresden University of Technology)

Do you ever find yourself venting to your favourite co-worker about rude customers, difficult patients, irritating colleagues? If so, I want to encourage you to keep doing exactly that. Sharing negative emotions in the workplace has recently been found to decrease your chances at developing burnout, an unhealthy state of exhaustion and emotional depletion nobody wants to experience. This is especially true for health care professionals, who deal with a lot of emotional distress in their daily work. When authentic emotional expression is encouraged and supported in a team or a work unit, we speak of a “climate of authenticity”. This blog aims to take a closer look at this fairly new concept: What makes team climate “authentic”? How can this protect our mental health? And can we train employers and employees to communicate safely, openly and authentically?

Introduction

The term “climate of authenticity” was proposed and defined by Grandey et al. (2012), as “the perceived acceptance of, and respect for, unit members’ expressing felt emotions when interacting with coworkers” (p. 3). This includes negative emotions just as much as positive emotions. In contrast to seeing negative emotions as uncomfortable, outright unprofessional, or something that brings the general team spirit down, a climate of authenticity embraces the expression of all kinds of feelings, as it allows us a break from constant emotional regulation (Grandey et al., 2012). As mentioned, this is especially important for people who work in close contact with customers, clients and patients, as this type of work demands the ability to handle various emotional needs and interpersonal conflicts on a regular basis. For health care professionals in particular, the biggest threats to their emotional stability at work are a) interpersonal mistreatment in the face of suffering and death (e.g. patients not being able to regulate their emotions and “lashing out”) and b) constant suppression of one’s own negative emotion in an attempt to show patients and their families compassion and empathy (Grandey et al., 2012).

A climate of authenticity can emerge “bottom-up”, for example as a result of the different personalities that make up a team unit, as well as “top-down” through training and supervisor feedback (Grandey et al., 2012). This results in the great advantage of being able to influence a team’s climate from the outside, for example through coaching and standardized interventions.

One approach that has been tested to foster authentic communication in a work unit is nonviolent communication, in short NVC.

NVC has four main components:

- the communication of non-evaluative observations

- the expression of feelings and needs

- clear requests

- empathic listening to dialogue partners (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018).

In the following I want to further illustrate the mechanisms through which a climate of authenticity can buffer against the negative outcomes of emotional labour and distress, and thus protect employees from burning out. Afterwards I will present the results of a pilot study on the effectiveness of NVC training for a group of health care professionals, and dive shortly into the emerging practical implications. In other words, the two main questions to be answered are:

- How can a climate of authenticity prevent employees engaging in emotional labour from burning out?

- Can authentic, non-violent communication be trained effectively?

Theoretical Model and Empirical Findings

Before we can look at how an authentic team climate may buffer against potential burnout, we have to understand the basic relationship between emotional labour and burnout. For health care professionals, one big stressor at work is mistreatment by patients and clients, which has already been shown to predict burnout (Dormann & Zapf, 2004). When we experience interpersonal conflict, something that is generally very stressful, we have to tap into psychological resources like self-esteem and social support to cope with the situation. When these resources are constantly used or threatened, we may experience primary resource loss in the form of anxiety and distress, and in the long run exhaustion and health impairments like burnout (Grandey et al., 2012). According to the resource-based model of stress (Hobfoll, 1989), this primary resource loss can lead to a downward spiral through secondary resource losses. Secondary resource losses occur when we use (ineffective) coping strategies that do not account for the primary resource loss (Hobfoll, 2002). To stick with the example of health care professionals, a typical coping strategy that only works in the short-term would be to suppress one’s own emotional response entirely. This strategy is commonly known as surface acting and has repeatedly been linked to burnout (Kim, 2020; Theodosius et al., 2021).

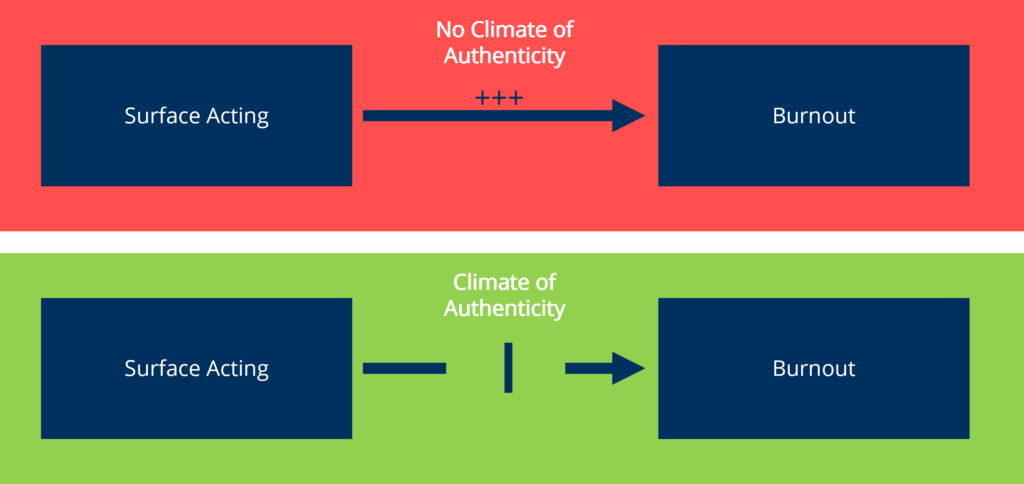

Now how can a climate of authenticity at team-level support us in regulating our emotions? The main idea is that an authentic communication style between colleagues allows employees to take a break from constant emotion regulation and surface acting, offering an opportunity to recover their resources and thus reducing the risk for emotional exhaustion, which is a facet of burnout (Grandey et al., 2012). In contrast, if a team does not encourage authentic communication, it is very likely that even “backstage” employees have to keep on a mask, in order not to violate any social norms within the team. This potentially even worsens the depletion of resources already experienced through mistreatment by patients and surface acting (Hobfoll, 2002) thus enhancing the risk of emotional exhaustion.

When authentic communication is supported on unit level and one is encouraged to share their feelings, employees can let go of self-monitoring and self-regulation and experience some relief, for example through venting to a co-worker. Grandey et al. (2012) were the first to verify the positive effect authentic communication has within a team, as they found high levels of climate of authenticity to buffer against the resource depletion (and emotional exhaustion as a consequence of it) of surface acting on the job. Plus, authentic communication in a work unit is believed to prevent interpersonal conflicts from rising up within the team itself, removing or at least reducing another potential stressor (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018).

Research is only beginning to explore methods to build or strengthen the climate of authenticity for a specific work unit. The concept of NVC (Rosenberg & Chopra, 2015) offers guidelines for safe and empathic communication, which also entails creating a certain emotional distance in order to allow adequate emotion regulation. This starts with communicating observations in a non-evaluative way. By leaving one’s own judgements out of the way when describing a particular behaviour or a situation we experienced, our dialogue partners are less likely to react with criticism or in a defensive way (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018). After establishing a rather objective view on the topic, one can begin to express their own feelings and unmet needs in regard to the situation. Ideally this is followed by a clear, but non-demanding request of action for their dialogue partner (Rosenberg & Chopra, 2015). When in the role of the empathic listener, one should “connect with them by first sensing what they are observing, feeling and needing, then we discover what would enrich their life” (Rosenberg & Chopra, 2015, p. 1). Empathic listening therefore involves understanding what is said explicitly and implicitly. This communication style surely can be demanding to adapt, as it requires emotional self-awareness, knowledge and vocabulary regarding different emotions, and the ability to listen with empathy while still protecting some sort of emotional distance (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018).

Given these circumstances, it seems plausible to develop a training program specifically for employees and their supervisors to become familiar with the concept of NVC and acquire some of the necessary skills to ultimately create a climate of authenticity.

The effects of such NVC training were just recently examined by Wacker and Dziobek (2018) who conducted a pilot study with German health care professionals, a group that is known to perform high levels of emotional labour while often staying silent about their struggles (Ramvi & Gripsrud, 2017). More specifically, they carried out a pre-post-intervention examining effects of their training via questionnaire three days, and a second time three months after the NVC training. An external NVC consultant was invited to construct and carry out the three day intervention that included theoretical input as well as practical exercises. The focus was set on the effective communication of negative emotions like frustration and anger, that usually stay supressed (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018).

They found NVC training to be effective in teaching important emotional and interpersonal skills, that are necessary to communicate positive as well as negative emotions safely and respectfully (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018). Most interestingly, the verbalization of negative emotions between colleagues increased directly after the training, and 3 months after the intervention the participants still reported an increase in communication skills in the work setting, and an overall decrease in social distress (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018). These results point at NVC training being a useful method to establish acceptance of expressed emotion, the basis of a climate of authenticity. They also support the idea that “top-down” strategies such as interventions and training can influence communication styles and skills, and ultimately be effective in creating an authentic team climate. Though NVC and a climate of authenticity are not the same construct by any means, these findings will hopefully inspire the construction of more targeted interventions with the goal to increase authenticity in a work unit.

Summary and Practical Implications

A climate of authenticity is characterized by an acceptance of the emotional expression that is shared on unit-level and includes feeling safe to share positive emotions as well as negative ones (Grandey et al., 2012). Working in a team which values emotional expression and authenticity can protect people who engage in surface acting and face interpersonal conflict or mistreatment on a regular basis from experiencing emotional distress, exhaustion and burnout (Grandey et al., 2012). By being able to express themselves freely, employees working in an authentic team climate can take a break from constant emotional regulation and replenish their resources. This finding is especially relevant to health care professionals, customer care and any profession requiring high levels of emotional labour.

Although a climate of authenticity that emerges “bottom-up” through the different personalities that come together in a work unit might be more effective in protecting employee’s mental health (Grandey et al., 2012), training employees in NVC can be an effective way to support authentic communication and free expression of negative emotions (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018).

Future research could be directed at developing interventions specifically targeted at increasing unit-level climate of authenticity, since NVC has a slightly different focus. In this regard, the evaluation results of an intervention which was developed at Technische Universität Dresden and which focuses on creating a climate of authenticity (Ledermann & Dörfel, 2022), are promising. To further explore this fairly new concept it could also be beneficial to study under which circumstances an authentic team climate can emerge naturally. Even though we cannot entirely stop mistreatment and interpersonal conflicts from happening in the workplace, an authentic environment can protect employees from taking damage once they have happened. Especially people who engage in a lot of surface acting as a reaction to these social stressors can benefit immensely from being supported by a team that respects and accepts emotional expression in the face of otherwise constant emotional regulation.

Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2004). Customer-related social stressors and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(1), 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.9.1.61

Grandey, A., Foo, S. C., Groth, M., & Goodwin, R. E. (2012). Free to be you and me: A climate of authenticity alleviates burnout from emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025102

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

Kim, J.‑S. (2020). Emotional Labor Strategies, Stress, and Burnout Among Hospital Nurses: A Path Analysis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship : An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 52(1), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12532

Ledermann, F., & Dörfel, D. (2022, 03. Februar). PENELOPE – Maßnahmen zur Förderung der seelischen Gesundheit in der Pflege: Emotionale Kompetenzen – Online Training. https://drks.de/search/de/trial/DRKS00026921

Ramvi, E., & Gripsrud, B. H. (2017). Silence about encounters with dying among healthcare professionals in a society that ‘detabooises’ death. International Practice Development Journal, 7(Suppl), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.7SP.009

Rosenberg, M. B., & Chopra, D. (2015). Nonviolent communication: A language of life: Life-changing tools for healthy relationships. PuddleDancer Press.

Theodosius, C., Koulouglioti, C., Kersten, P., & Rosten, C. (2021). Collegial surface acting emotional labour, burnout and intention to leave in novice and pre-retirement nurses in the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Open, 8(1), 463–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.649

Wacker, R., & Dziobek, I. (2018). Preventing empathic distress and social stressors at work through nonviolent communication training: A field study with health professionals. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000058