Morality in Selection Decisions

by Anna Maria Steffen (2nd semester Master Psychology – Human Performance in Sociotechnical Systems, Dresden University of Technology)

Job interviews are usually constructed in a way to test the applicants’ skills and abilities, to get a sense of their work motivation and experience and deduce if they would be the right fit for the position. In recent years, ethical scandals have led many organizations and recruiters to pay attention to job candidates’ morality, as well (Yam, Reynolds, Wiltermuth, & Zhang, 2021, p. 2). One may think of the Lehman Brothers scandal or Enron, or, looking at more recent years, the Wirecard scandal in 2020 or the recent scandals at Credit Suisse in 2021 might come to mind. The way in which ethical scandals can harm the reputation of a company and have an enormous impact on their success or failure has led to preventative measures such as the expansion and refinement of the personnel selection processes. This text aims (a) to give a brief overview of recent findings by Yam et al. (2021) on how morality is perceived in the personnel selection processes, and (b) to take a look at the different work areas in which moral lapses are strikingly more frequent. It also takes a brief look on “faking” in personnel selection processes, i.e. if interviewees try to feign higher morality than they actually possess.

Introduction

Yam et al. (2021) examined the signals job applicants might give indicating their morality and the way these signals might raise their appeal to interviewers. They wanted to challenge the belief that positive signals of morality always increase applicants’ appeal to interviewers. In the study, they hypothesised that candidates’ signals of morality interact with the nature of the industry, such that candidates who send signals of morality are less likely to be selected for jobs in a morally tainted industry, compared to neutral candidates (Yam et al., 2021, p. 1). They conducted four experiments which will be briefly explained here.

Generally, they described that in practice, interviewees could show their morality in many ways, such as integrity tests (integrity tests are instruments that are used for personnel diagnostics for the purpose of measuring the integrity of an applicant and thus being able to predict possible damaging behavior in the workplace – often used in banking, auditing and security), but also by talking about previous moral behaviour or listing affiliations with moral groups on their résumés. While integrity tests positively predict overall job performance (Sackett & Harris, 1984) and thus signalling morality should benefit candidates, there has also been research suggesting that people are often derogated or even punished for expressing their morality. For example, Monin, Sawyer, and Marquez (2008) found that moral people can elicit a sense of moral reproach, leading to a lower likability. So the question is, does morality increase applicants’ chances or might it even be a disadvantage to depict oneself as a moral person?

Empirical Findings

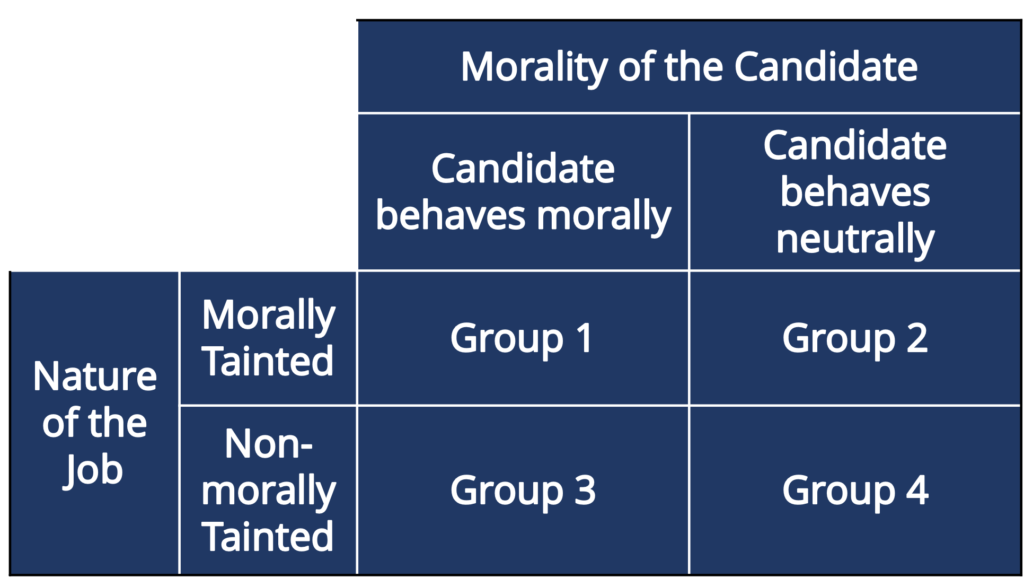

1 In the first of the four experiments, professional interviewers who work in personnel selection/recruitment in the US were questioned. Yam et al. (2021) used a 2 by 2 between-subjects design, controlling for ‘morality of the candidates: candidate behaves morally vs. candidate behaves neutrally’ and ‘nature of the job: morally tainted vs. nonmorally tainted’. Participants were given a brief description of a job vacancy and were then shown a video in which a professional actress played the interviewee. Afterwards, participants rated the job fit and hireability of the candidate. The actress either showed signals of acting justly – specifically, she recalled an event in which one of her coworkers was acting immorally but she refused to engage in the immoral behaviour, even though it personally benefited her (condition: candidate behaves morally). Or, in the neutral condition, the interviewee described working with a challenging, but not immoral coworker. In the morally tainted work condition, participants were told that the interviewee was applying for position in a large tobacco industry. Ashforth and Kreiner (1999) had shown priorly that the tobacco industry is regularly viewed as stigmatized and identified as a dirty industry. In the nonmorally tainted work condition, participants were told that the interviewee was applying for a position in a large retail company.

Results showed that when the candidate signalled morality, it significantly increased her perceived job fit in nonmorally tainted (=neutral) industry conditions. In the morally tainted industry, the morality reduced the perceived job fit, the moral job candidate (Group 1) was evaluated worse than the neutral candidate (Group 2). When an industry was non-morally tainted, the hireability of moral candidates (Group 3) was significantly higher. In summary, this provides support for the hypothesis: Candidates who signal their morality (Group 1 and 3) are perceived as less hireable in morally tainted industries (Group 1) because of a perceived lack of job fit.

2 In the second experiment, the authors wanted to examine whether interviewers who work in a morally tainted field (Group 1 and 2) would respond similarly or if they would try to defend their industry’s moral image. They sent their experimental materials to a large tobacco manufacturing company in Southwest China. The design was similar to experiment 1: a 2 by 2 design with similar conditions. To mask the true purpose of the study, Yam et al. (2021) used a cover story of an American college graduate looking for employment in China, so participants would think it was about the evaluation of a foreigner as a prospective job candidate. In the morality condition (Group 1), the candidate received first place in an international business ethics case competition and the Better Business Bureau Student of Integrity Scholarship. In the neutral condition (Group 2), the candidate received first place in an international business case competition and there were no mentions of ethics.

The second experiment showed very similar results to the first one: in morally tainted industry, moral candidates were perceived to have a lower job fit than candidates with neutral morality. Using samples from the US and China, these findings suggest that job candidates can be seen as “too strongly associated with morality to be attractive candidates in morally tainted industries” (Yam et al., 2021, p. 13).

3 In the third experiment, the authors wanted to test whether unethical job candidates had a competitive advantage in morally tainted industries. They presented the participants with a letter of recommendation by a former supervisor with manipulated signals of the candidate’s morality.

There were three conditions:

- In the immorality condition, the immoral job candidate was willing to treat customers unjustly multiple times in order to help the organization succeed.

- In the moral condition, the candidate demonstrated a strong sense of fairness for the customers.

- In the neutral condition, only amoral information about the candidate was provided.

Results showed that immoral job candidates were consistently rated less hireable regardless of the industry manipulation, compared to moral and control candidates. This proved that candidate’s immorality did not provide a competitive advantage even in morally tainted jobs. The findings show indications that while signalling morality in interviews can reduce the chance of being hired, so can signalling past immoral acts – even if those acts were performed to help the company. When interested in pursuing careers in morally tainted jobs, according to this study, candidates should be careful not to suggest that their moral character is either too strong or too weak, but rather try to find a balance.

4 In the fourth experiment, the authors wanted to explore whether there would be similar results in other industries, not only focusing on the tobacco industry, but on oil and gas. They manipulated mission statements that the participants were shown, indicating either that the oil and gas company set high standards in ethical behaviours as well as performance excellence, or that they only set high standards in performance excellence, indicating nothing about ethical convictions. Results showed that when the organization’s mission statement was framed in moral terms, morality in candidates positively predicted their likelihood of being hired via perceived job fit. When the mission statement was framed in economic terms, the pattern reversed. This shows that when a company in a morally tainted field has a mission statement framed in moral terms, moral candidates not only are not penalized, but actually receive better ratings of hireability.

This has major implications for organizations within a morally tainted field that want to redirect the path of the industry and become an example of industry with moral employees. According to Yam et al. (2021), they should phrase their mission statement in such a way that they highlight moral values as an asset for the organization. In that way, they might not only encourage moral candidates to apply because they self-identify with the corresponding statement, but they might also change the perception of moral candidates in the eyes of the interviewers and make it more likely for the personnel to consist of moral employees.

However, the study of Yam et al. (2021) used as a basis mostly the immoral perception of a certain industry using biases concerning certain industries. They did prove with their fourth experiment that companies in an immorally tainted field might also present themselves as moral and change the perception from outside – however, they did not look at a variety of industries to compare which ones show moral inferiority. That’s why in this text, we want to take a closer look at the industries this might be especially relevant to.

Which industries have in recent years shown more frequent moral lapses and ethical scandals? You could say, if certain fields are more prone to ethical scandals, it might be even more important for associated companies to test their potential employees’ morality beforehand, as to not risk the company’s integrity and reputation. Of course, companies might not adhere to hiring principles that would be ethical rather than ecological – they might do quite the opposite. After all, ethical scandals are often not the fault of individual immoral workers, but rather the leaders neglecting to uphold ethical standards. Still, it might be interesting to have an overview of certain work areas more prone to ethical scandals. It might give us an idea of areas which would be especially interesting to explore concerning processes of (un-)ethical decisions. These would be key areas to implement personnel selection strategies, as well.

The Institute of Business Ethics published an overview in January that showed ethical concerns and lapses recorded for IBE’s media monitoring exercise in 2021. The report provides an analysis of 2021’s trends and serves as a starting point to pinpoint work areas that might suffer from more frequent lapses in morality. In their report, they stated that in 2021, the Technology sector showed the most ethical lapses, with the most concerning issues being data protection and privacy. Banking and finance had only a few less ethical lapses recorded in the media in 2021, but still came in second with issues like behaviour and culture as well as treatment of customers and employees, bribery and corruption. The third place is taken by retailers and consumer goods with prevalent issues being product safety and quality (Institute of Business Ethics, 2022).

The report only counted media representations of ethical scandals, but this does not represent all morally questionable decisions of companies. For example, a tobacco company could be really bad for the health of many people, but as that lies in the nature of the product, it would not make the news. Nonetheless, the issues frequently reported point to the question whether better personnel selection or earlier assessment of a potential employee’s morality might improve the enforcement of ethical standards in different work fields. Or if, like Yam et al. (2021) suggest, candidates with higher presenting morality might just be perceived as unfit for certain positions.

Of course, another question is if the morality presented in job interviews actually corresponds to moral behaviour shown in everyday life. Questions concerning the susceptibility of assessment tools for “faking” or impression management are a popular point of discussion amongst personnel psychologists. Viswesvaran and Ones (1999) found evidence that selection procedures such as personality tests are fakable. Birkeland, Manson, Kisamore, Brannick, and Smith (2006) found that they appear to be faked to some extent in actual selection settings. The topic is too extensive to deal with adequately in this text. But the question remains how much of reported moral behaviour in job interviews is faked or can be faked, so that some parts of the personnel selection process could include components, where faking would be reduced, like personality tests or questions with forced-choice answers or a warning not to fake. We now know that feigning morality might actually not be to the potential employee’s advantage, depending on the field for which they search for work in.

Summary

As has been shown in recent studies, not all employers use morality as a beneficial factor in candidate interviews. In general, people can and do fake certain personality aspects in job interviews. Morality is not necessarily seen as an asset for all job prospectives, though. Interviewers might see candidates as “too moral” for certain positions in morally tainted industries, thinking the candidates would not fit the company. Companies in morally tainted industries that would like to purposefully change their selection processes, could publish mission statements underlining their moral standards and ethical values.

Industries that have made immoral decisions in the last years that have led to media-effective ethical scandals are mainly the Technology sector as well as Banking and Finance. For companies in these industries, it might be even more important to think about which principles they want to embody and if it might be time to implement new selection processes.

Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (1999). “How Can You Do It?”: Dirty Work and the Challenge of Constructing a Positive Identity. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202129

Birkeland, S. A., Manson, T. M., Kisamore, J. L., Brannick, M. T., & Smith, M. A. (2006). A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Job Applicant Faking on Personality Measures. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 14(4), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00354.x

Institute of Business Ethics (2022, January 24). Business Ethics in the News 2021: Business ethics briefing. https://www.ibe.org.uk/resource/business-ethics-in-the-news-2021.html

Monin, B., Sawyer, P. J., & Marquez, M. J. (2008). The rejection of moral rebels: Resenting those who do the right thing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.76

Sackett, P., & Harris, M. (1984). Honesty Testing for Personnel Selection: A review and critique. Personnel Psychology, 37(2), 221–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1984.tb01447.x

Viswesvaran, C., & Ones, D. S. (1999). Meta-Analyses of Fakability Estimates: Implications for Personality Measurement. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131649921969802

Yam, K. C., Reynolds, S. J., Wiltermuth, S. S., & Zhang, Y. (2021). The benefits and perils of job candidates’ signaling their morality in selection decisions. Personnel Psychology, 74(3), 477–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12416